|

Making Sense of the Information Ecosystem

A new THB series for 2026 - Part 1, Democracy and Propaganda

One of the most common questions I get is, “How do I know what is true and what is not?”. In 2026, it is a question that all of us struggle with — Even experts are ignorant about most things.

I respond to this question by saying that I don’t have a simple answer or formula, but that there are better and worse ways to arrive at beliefs more likely to be accurate. In my courses, I explain to students that a very good starting point is to understand the roles of information in democratic politics, and in particular, why “facts” are inevitably contested and how “truths” are emergent and manufactured.

Today’s post kicks off a new THB series that I expect to run well into 2026 — Making Sense of the Information Ecosystem — as I begin pulling together a sequel to The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics, my 2007 book that gives THB its name.¹

I start the series by introducing some concepts that will help us to together make sense of the information ecosystem which we can characterize using a well-known framework introduced by political scientist Harold Lasswell in 1948:²

Who gets to speak credibly;

What messages survive amplification;

Which channels dominate attention;

To whom the messages are targeted;

What effects result.

More generally, an information ecosystem is the interconnected system of actors, institutions, technologies, norms, and incentives through which information is produced, selected, transmitted, amplified, interpreted, and acted upon within society.

As Walter Lippmann observed in his classic book, Public Opinion, in 1922, the goal of democracy is not to get everyone to think alike, it is to get people who think differently to act alike.

In his 1992 introduction to Lippmann’s Public Opinion, Michael Curtis explained the significance of Lippmann’s distinction between “the world outside” and the “pictures in our heads”:³

The real external environment is too big, too complex and too fleeting for direct acquaintance by citizens. The public can never fully understand political reality, “the buzzing, blooming confusion” of the world, partly because individuals could only devote a short amount of time to public affairs and partly because events have to be compressed into very short messages. In a letter dated May 18, 1922, Lippmann wrote that the bulk of public questions “deal with matters that are out of sight, and have therefore to be imagined.”

Common among Lasswell, Lippmann, and other pragmatists was an understanding that the task of politics is not to discover a singular truth that everyone believes, but rather to secure the collective agreement necessary for action in pursuit of shared interests.⁴

Securing agreement on action in a democracy — for instance on vaccine schedules, energy policy, U.S. intervention abroad — goes far beyond consideration of “facts,” even as reliable knowledge is essential to reliably connect actions with intended consequences.

In 2025, Dan Sarewitz provided a more contemporary take on “truth” consistent with that of Lippmann and Lasswell a century earlier:

Politically controversial issues are never settled by Galilean, E=mc² truths. Instead, truths are continually negotiated through the institutions of democracy. Scientists — “experts for the affirmative and experts for the negative” — are participants in the negotiation process, but often it is judges, juries, lawyers, elected officials, bureaucrats, advocates, journalists, and voters who determine what counts as truth.

From this perspective, central to the information ecosystem is propaganda — which, despite its pejorative connotations in common parlance, is fundamental to securing collective agreement in support of shared action.

Propaganda, according to Lasswell’s widely cited 1927 definition:

“is the management of collective attitudes by the manipulation of significant symbols.”

There is a lot in that little sentence, so let’s unpack it.

By collective attitude Lasswell means more than what is commonly called “public opinion,” to refer more broadly to a “tendency to act.” Collective attitudes are more than what people think, but informs their orientation to action.

An obvious example is voting. Presidents are not elected simply through views captured in opinion polls. If they were, then elections would be unnecessary. Election outcomes result from the actual act of voting, an expression of a collective attitude.

Election propaganda is focused on shaping collective attitudes in a way that favors one candidate over another at the ballot box. Politicians, consultants, and other seek to shape collective attitudes through the “manipulation of significant symbols.”

The concept of a symbol was usefully defined by Edward Sapir in the 1934 Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences.⁵ Sapir distinguishes referential symbols from condensational symbols.

Referential symbols are “economical devices for purposes of reference” — such as the abbreviation CO for Colorado, or a STOP sign to mean “stop your car at this intersection.” Referential symbols are necessary for communication, but are not imbued with deeper meaning.

In contrast, a condensational symbol is imbued with meaning — Like the three images at the top of this post.

The swastika is a condensational symbol. The helmet of the Dallas Cowboys is as well, as is the Christian cross and the Jewish Star of David. So too are the red hats exclaiming, “Make America Great Again.” When people display or burn a flag — whether it be American, Israeli, or Palestinian — it carries with it a meaning far beyond that expressed by displaying or burning a flag-sized, non-descript piece of rectangular cloth.

We are awash in symbols, both referential and condensational, which is how we interpret that part of the world that we do not experience directly — which is almost all of it.

Lippmann explained:

The only feeling that anyone can have about an event he does not experience is the feeling aroused by his mental image of that event.

I can guarantee that every reader of THB has some sort of feeling about Donald Trump. However, I’d guess that precious few of us actually know the President. President Trump is of course a real live person, but he is also a powerful condensational symbol — Yes, people can also be symbols.

For most everyone, our feelings about Trump (or any other leader or prominent person) are grounded not in truth but rather in the “pictures in our head,” which may or may not correlate well with reality.

Lippmann explains why symbols matter in politics:

Because of their transcendent practical importance, no successful leader has ever been too busy to cultivate the symbols which organize his following. . . Because of its power to siphon emotion out of distinct ideas, the symbol is both a mechanism of solidarity, and a mechanism of exploitation. It enables people to work for a common end, but just because the few who are strategically placed must choose concrete objectives, the symbol is also an instrument by which a few can fatten on many, deflect criticism, and seduce men into facing agony for objects they do not understand.

Significant symbols are those that play a key role in politics. Political actors manipulate such symbols in hope of shaping collective attitudes. This is propaganda.

Lasswell explained that propaganda has four functions:

to mobilize hatred against the enemy;

to preserve the friendship of allies;

to preserve the friendship and, if possible, to procure the cooperation of neutrals;

to demoralize the enemy.

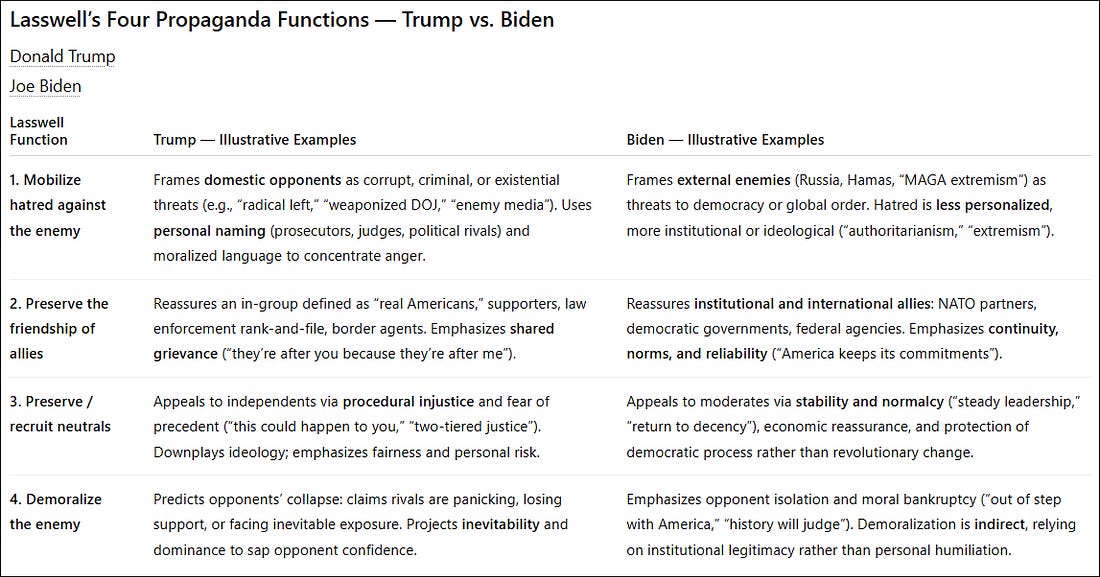

I asked ChatGPT to analyze President Trump’s use of propaganda as compared to President Biden, using Lasswell’s four-part framework. The results are in the table below:

There can be little doubt that Donald Trump is a master propagandist — regardless what anyone might think about him or his actions.

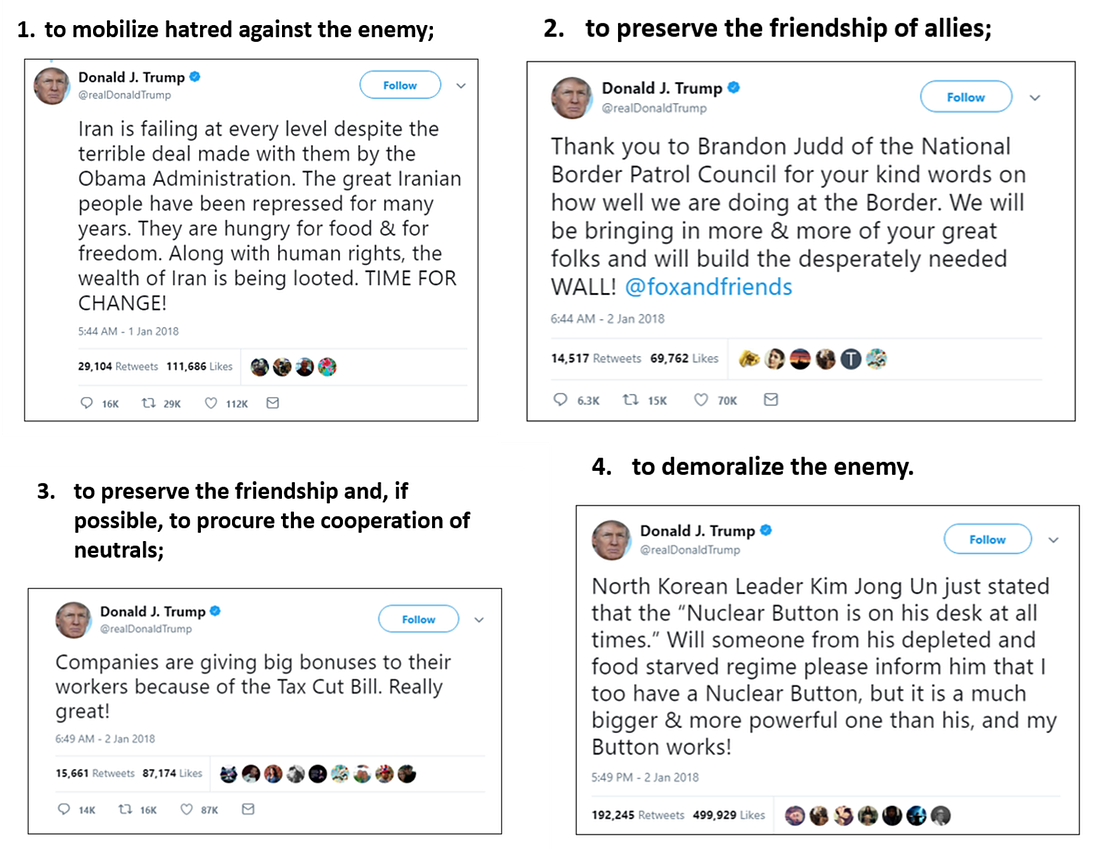

In my courses which covered propaganda, we would go through Trump’s Twitter posts, and just about every one of them fits into the four Lasswellian categories. For instance, below are four Trump Tweets from a 2018 class lecture of mine that illustrate Trump’s propaganda technique in terms of the Lasswellian categories, which offer a remarkable fit.

Propaganda is neither good nor bad, but a necessary element of a functioning democracy. That means that the only way to counter propaganda is not to try to eliminate it — not even possible — but with better propaganda, where better means more effective in shaping collective attitudes.⁶

Before closing for today, let me head off one common criticism of (philosophical) pragmatism as helping us to understand the role of information in politics. None of the above should be interpreted as abject relativism. There are of course truths — vaccines work, airplanes fly, nuclear power plants provide enormous amounts of electricity. There are also falsehoods — climate change is a hoax, chemtrails are a thing, Elvis lives.

Effective governance in a democracy depends upon aligning truths with collective action, but democratic governance is not necessarily effective. Democracy is hard work.

Reconciling modern society’s need for expertise to reliably inform collective action with left or right populist impulses that may reject expertise (or even truths) is perhaps the defining challenge of our time, and one that will be explored in depth throughout this series.

I hope you will come along and participate as this series develops!

The bottom line, for today:

Democracy means people acting together in pursuit of shared interests;

People act together based on collective attitudes;

Collective attitudes are typically created and shaped not through direct experience, but through communication;

Political communication is grounded in significant symbols;

The manipulation of significant symbols in an effort to shape collective attitudes is propaganda;

Propaganda is fundamental to the information ecosystem and thus democracy.

Comments, questions, critique all welcome!

Please click that “❤️ Like” button — More likes mean that THB rises in the Substack algorithm and gets in front of more readers. More readers mean that THB reaches more people in more places, broadening understandings and discussions of complex issues where science meets politics. Thanks!

THB exists because of its paid subscribers, who also get to participate in discussions under all posts, like this one. Please consider an upgrade!

As honest brokering is a group exercise, I always appreciate your participation — comments, critque, suggestions. For the sequel to THB, I am aiming for 2027, which is a nice and neat 20 years after THB was first published.

Lasswell, H. D. 1948. The structure and function of communication in society. The communication of ideas, 37:136-139.

Lippmann’s characterization is of course a version of Plato’s allegory of the cave.

Here, “agreement” does not mean universal agreement, but rather, the degree of agreement necessary under a particular democratic order for action to occur. In the United States at the federal level, achieving such an agreement requires clearing a fairly high bar — a majority in the House, a super-majority in the Senate, a presidential signature, and survival of court challenges.

Sapir, E. 1934. Symbolism. Encyclopedia of the social sciences, 14:492-495.

Some in the expert community have sought to self-appoint themselves as arbiters of truth claims (e.g., in "so-called “misinformation research” and “fact checking”) in an effort to manage propaganda, and perhaps even circumvent the messiness of democracy. Such efforts are of course a form of propaganda and subject to the dynamics of the information ecosystem just like all truth claims. This series will explain why such efforts are doomed to fail (on their own terms) and are ineffective if not counterproductive.

You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.