|

This is the second installment of THB Subscriber Questions. If you have a question that you’d like me to address in a future THBSQ post, just enter it in the comments below. If I didn’t get to your question this month, please ask again. I’ve identified a few that will be the subject of full-length future posts, including my views on current challenges to universities and an update on COVID origins.

On to the Q&A . . .

Anonymous (X/Twitter): Where is your line that differentiates a scientific consensus from a political consensus? What indicators do you look for?

Twenty years ago (tomorrow, in fact), I had a letter in Science responding to Naomi Oreskes claim that the “scientific consensus” on climate change meant universal agreement, with no dissent.

I countered by arguing that a “scientific consensus” is actually a characterization of a distribution of views.

A consensus is a measure of a central tendency and, as such, it necessarily has a distribution of perspectives around that central measure. On climate change, almost all of this distribution is well within the bounds of legitimate scientific debate and reflected within the full text of the IPCC reports. Our policies should not be optimized to reflect a single measure of the central tendency or, worse yet, caricatures of that measure, but instead they should be robust enough to accommodate the distribution of perspectives around that central measure, thus providing a buffer against the possibility that we might learn more in the future.

While the IPCC does not define “scientific consensus,” the view I present is consistent with how the IPCC characterizes its reports (emphasis added):

In Assessment Reports, Synthesis Reports, and Special Reports, Coordinating Lead Authors (CLAs), Lead Authors (LAs), and Review Editors (REs) of chapter teams are required to consider the range of scientific, technical and socio-economic views, expressed in balanced assessments.

Some findings of the IPCC have a narrow distribution with a clear central tendency — Such as: the Earth has warmed over the past century. In contrast, some findings are wide with no clear central tendency — Such as: projected tropical cyclone activity in 2100. There are many different distributions of views associated with each IPCC finding (of which there are many thousands) and therefore no such thing as a uniform “consensus” on all things climate.

A “political consensus,” in contrast is typically defined by the accepted rules of decision making in a particular context. A 5-4 ruling of the Supreme Court in principle carries as much legal weight as 9-0. In politics, as in science, a consensus can change. In fact, such change is a defining feature of both science and democracy.

Scott T: Has there ever been another industry that has successfully used policy to drive invention and new technology? I don’t know of any. However this is what the energy industry is trying to do. What types of policy do you propose to create a more balanced approach to decarbonization?

Yes. The three best examples that I frequently cite are public health, agriculture, and defense. Human life spans have doubled over the past century. Agricultural productivity has increased dramatically over the same span. Arguably, the most powerful innovation enterprise in human history has been the U.S. Department of Defense.

Energy policy would benefit from implementation of key lessons of these success stories. Among them, public policy and private enterprise can be mutually reenforcing; long-term progress requires sustained incremental gains; and sustained political support backed by public accountability keeps progress on track.

I have had a book-length project on exactly this topic on the back burner — Maybe this broad subject will make for a good future emphasis for THB.

Charles L: I wish you would turn as critical an eye in the direction of those arguing for increased use of fossil fuels and all that goes with it as you do to those deeply concerned about the consequences of our present path. I am looking forward to your addressing those who are on denial about what may be happening.

Over the weekend I had brunch with a well-known environmental advocate who asked me the same question. I’ll respond here as I did to him — I do, but those critiques rarely get much attention.

Some examples:

Steve Koonin — Book review of Unsettled

Steve Koonin — Public debate at UNC on “net zero”

Alex Epstein — Book review of Fossil Future

Bjorn Lomborg — My critique of his “climate engineering” proposals

There are other examples as well. However, there is no doubt that I see the scientific integrity of leading, authoritative institutions to be far more important than the views of individual advocates. So, for instance, the IPCC, NAS, leading journals, and government institutions are where I focus most of my efforts. They simply matter more for scientific integrity, policy making, and public confidence in science.

Jason: Roger, you’ve done yeoman’s service in defending climate science and the integrity of science-based institutions even at great personal cost. It’s pretty clear to me that the predominant threat to these domains has switched along with the US government. Would you agree and are you planning on addressing this head on?

This is a great question and one I think about a lot. As readers here well know, I am no fan of Donald Trump or the Trump administration. My main complaint is that they have no apparent interest in policy making or following the precepts of U.S. constitutional governance.

In contrast, I am a big fan of the U.S. Constitution. I also think that both major U.S. political parties have failed comprehensively, over a time longer than Trump’s reign. Engaging in partisan conflict seems pretty useless at the moment, although I fully understand its draw. Other than a desire to wield governmental power, I believe that both the Democatic and Republican parties are soulless at the moment, bereft of core values. We should do better.

Where I am at: Good ideas still matter. Scientific integrity matters. We experts need to get our own houses in order, regardless what politicians may do. We need better leadership — in institutions of expertise (over which we experts exert some control), but also in government (in which we do not). The MAGA fever will one day break and we will need to restore/rebuild/reassert constitutional governance — Perhaps the 1870s and 1970s offer some precedent. These are the background thoughts that shape my work here at THB. Perhaps that will change, but that is where I’m at.

All that said, I’ll continue to moderate THB comments to avoid pro- or anti- MAGA cheerleading — or really, any political cheerleading. There are plenty of places for that. THB won’t be one of them.

Jeff R: I applaud your challenge of NOAA on financial impacts of extreme weather events. But there are many other examples of government agencies bias. One example is EPA’s website communications regarding the heatwave index, progressively burying the index dating back to 1895 with one beginning in 1960 and only covering 50 selected cities . . . Should there be more effort to challenge these distorted presentations of information, some directed as teaching materials for students?

One of the mysteries of the climate issue that has baffled me for a while is how few scientists are willing to hold our own community to account for bad science. If I had a dollar for every time an expert told me quietly behind-the-scenes that they agree with my critiques of RCP8.5, NOAA”s “Billion Dollar Disasters,” the ICAT Frankenstein dataset, extreme event attribution . . .

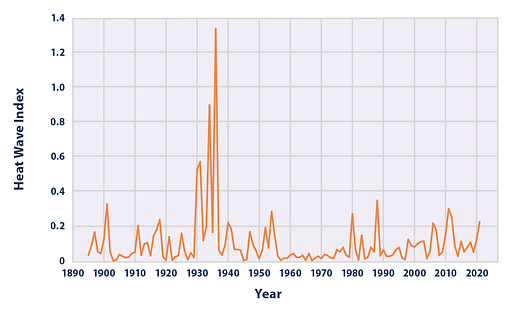

On EPA and heat waves, here is a fun fact — the time series that you reference that EPA uses to document heat waves dating to 1895 in an update from a figure in a paper of ours from 1999.

That paper — one of my most cited — was co-authored with Ken Kunkel and Stan Changnon (RIP) and comprehensively reviewed trends in weather and climate extremes associated with human and economic impacts in the United States.

Kunkel, K. E., Pielke Jr, R. A., & Changnon, S. A. (1999). Temporal fluctuations in weather and climate extremes that cause economic and human health impacts: A review. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 80(6), 1077-1098.

We concluded:

This review shows that most measures of the economic impacts of weather and climate extremes over the past several decades reveal increasing trends in losses reaching a peak in the 1990s. This includes property and crop losses due to floods, hurricanes, thunderstorms, and winter storms. However, trends in the frequency/severity of most related atmospheric phenomena do not exhibit comparable increases with time. . . the increasing financial losses from weather extremes are primarily due to a variety of societal changes. These include population growth along the coasts and in large cities, an overall increased population, more wealth and expensive holdings subject to damage, and lifestyle and demographic changes exposing lives and property to greater risk.

You are correct that EPA leads its heat wave index homepage with a figure that shows heat waves starting in 1960, which as you can also see in the figure above, do show an increase since 1960. The indicator based on our paper shows that the 1930s, by far, were the most extreme decade for heat waves in the U.S. since 1895.

EPA plays things straight in their description of the shorter-term data:

As cities develop, vegetation is often lost, and more surfaces are paved or covered with buildings. This type of development can lead to higher temperatures—part of an effect called an “urban heat island.” Compared with surrounding rural areas, built-up areas have higher temperatures, especially at night. Urban growth since 1961 may have contributed to part of the increase in heat waves that Figures 1 and 2 show for certain cities. This indicator does not attempt to adjust for the effects of development in metropolitan areas, because it focuses on the temperatures to which people are actually exposed, regardless of whether the trends reflect a combination of climate change and other factors.

My main critique is that this data is characterzed as a “climate change indicator” — Clearly, it is not.

This post, like all posts here at THB, has been brought to you by the paid subscribers of THB, whose support makes THB possible. This was reenforced to me by the results of my recent paid subscriber poll in which 0% of paid subscribers requested more paywalled content. If you value THB and the work it brings to the public, please consider joining the paid subscribers as a THB supporter!

You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.