|

|

Thanks to Myra’s comment, we checked out the technical report from the ECDC 2023 on the Investigation protocol for human exposures and cases of avian influenza.

Myra points to Annexe 6, which identifies the extensive knowledge gaps in human cases of avian influenza.

However, on page 9, a vital piece of the puzzle is presented: developing a case definition.

The proposed case definition section highlights the challenges of distinguishing between actual active infections in humans and contaminations following detections in people exposed to infected animals or contaminated environments. TTE has been discussing these issues for some time.

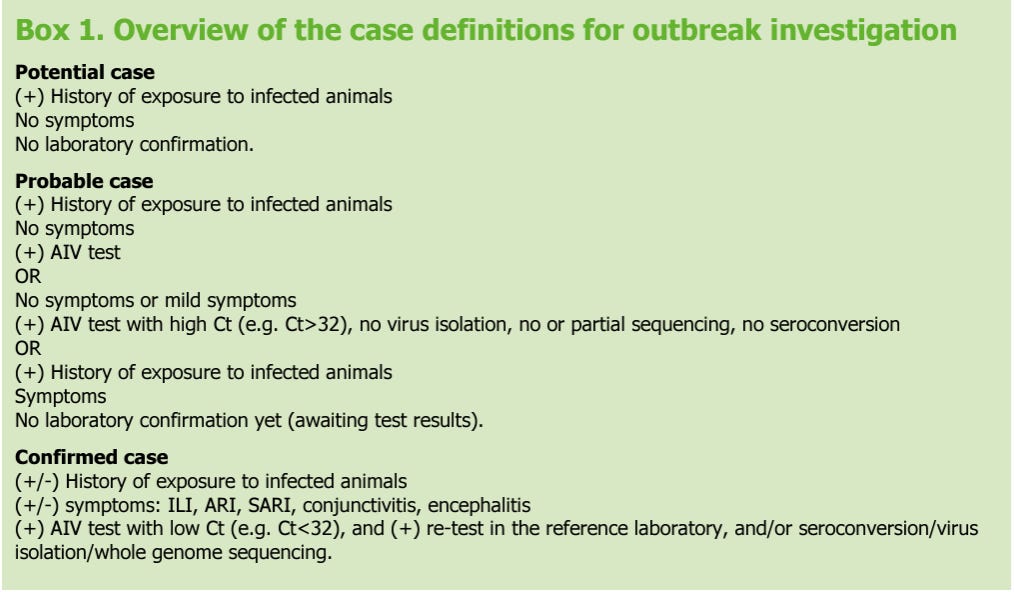

The ECDC proposes three definitions for a potential, probable or confirmed case.

A potential case may be defined as any person with a history of exposure to infected animal cases who does not have symptoms or laboratory confirmation.

A probable case may be defined as a person with a history of exposure to infected animals AND a positive AIV laboratory test result but no symptoms OR a person who is symptomatic pending laboratory confirmation OR a person who is asymptomatic/very mildly symptomatic with a positive AIV laboratory test result with high Ct value (e.g. Ct>32), but no virus isolation and no serological evidence of infection.

A confirmed case may be defined as a person with or without a known history of exposure that has a positive AIV laboratory test result with a low Ct value (e.g. Ct<32) that retested positive (preferably at a national influenza reference laboratory), and who has developed symptoms.

This definition moves the bar on the lack of definition required to be considered a covid case during the recent pandemic. According to the WHO, all that was needed to be a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 case was a positive PCR test regardless of clinical criteria.

Once we use a definition that includes a low Ct as a measure of infectiousness, the dynamics of those considered positive change, so when commentators write that ‘out of the 57 confirmed infections in the US in the past year, all have been mild and none hospitalised,’ they fail to address whether the individuals were infectious.

Reviewing the US-confirmed cases reveals they do not meet the definite case criteria. For example, the CDC reports low viral RNA concentrations in clinical specimens and unsuccessful attempts to isolate the virus in culture. Our analysis of the UKHSA review cases shows that none of the proposed human transmission cases would meet the definite criteria.

Because the WHO definition is ambiguous and unable to determine infectiousness, the notion of a ‘confirmed case’ should be assigned to the bin. Moving to a criteria that requires a ‘definite case’ would move us closer to an evidence-based approach that permits a clearer understanding of what is happening.

With one or more iterations of this case definition, we might make progress. To move the dial even further forward, TTE recommends that case definitions be tested against viral culture.

There is little incentive to develop an accurate method for diagnosing respiratory infections. Reliable case information will not be good for business as it won’t benefit those commentators, modellers, and speculators who thrive on such unreliable definitions. It will also not be welcomed by the pandemic industry as they thrive on dubious data for fueling stockpiles and the purchase of ineffective treatments.

This post was written by two old geezers who dislike sloppy case definitions.

You're currently a free subscriber to Trust the Evidence. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.