At least five interesting things: Will of the Masses edition (#55)Abandoning X; Drone world; Asian voters' rightward shift; China and the Global South; Polycrisis; Illegal immigration's fiscal impact; Iranian power

In recent weeks I’ve started trying to determine a “theme” for each of these roundup posts. Tying them all together somehow is a fun challenge! The last one was a bunch of nerdy econ papers. Today’s items have more to do with public opinion. But first, podcasts. I recently went on the Bulwark’s podcast, Beg to Differ. I talked about a lot of stuff, but the headline ended up being about why Tulsi Gabbard is scary:  I also have an episode of Econ 102, where Erik and I discuss various posts I’ve written recently:

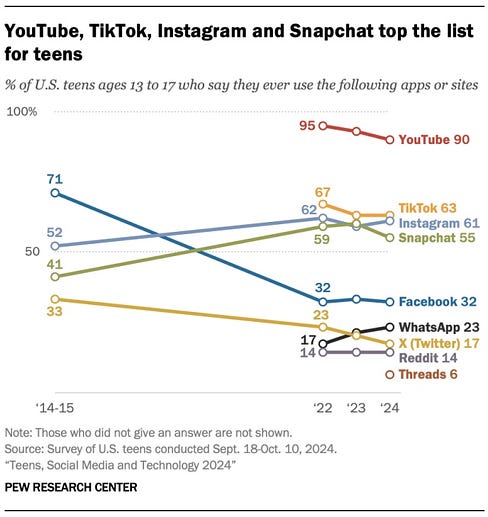

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things! 1. Young Americans (and Americans in general) are abandoning XPew has a new survey out about social media use among American teenagers. Here’s the key chart:

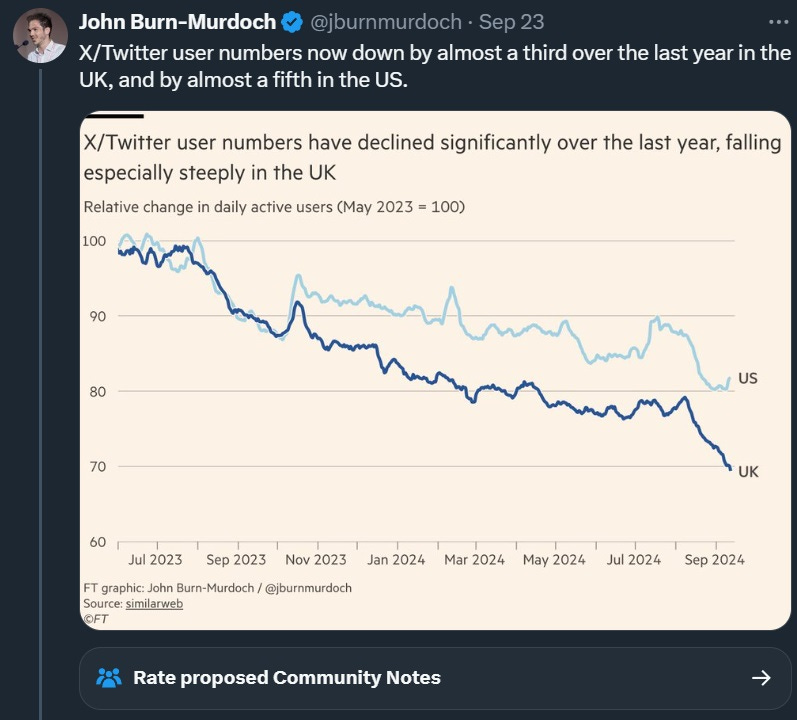

Interestingly, there’s possibly some sign that young people are using less social media in general than in 2022. That might correspond to the end of the pandemic and the resumption of real-life interaction, or it might be a response to the general realization that public social media platforms are toxic and unhealthy. Note that the only significant gains in the last 2 years came from WhatsApp, which is a small-group chat service rather than a public platform. But anyway, the most striking finding here is that two of the big dominant platforms of the 2010s — Facebook and X (Twitter) — have become much less popular among teens. But Facebook isn’t doing too badly here — it saw its big plunge in teen usage in the 2010s, and a lot of that was probably just young people switching to Instagram. And it’s still holding steady at 32%, which is surprisingly robust. But X is getting absolutely crushed. It had already declined substantially from the 2010s, but in the last two years it looks like it’s lost over a quarter of its teen user base. This is consistent with what I’ve seen on the platform. The humor, silliness, pop cultural references, creative memes, and personal life updates that I associate with young users are mostly gone — no matter where I look, I just see middle-aged people shouting about politics. Maybe X just isn’t the place for young people — maybe it’s just naturally suited to adult topics. But in fact, data from Similarweb suggest that the decline isn’t just among the youth: Anecdotally, I noticed that some of the most important recent news events — the fall of the Assad regime in Syria, the arrest of Luigi Mangione, and the panic over drones in New Jersey — reached me through group chats well before they appeared in my X feed. The app’s basic function as a real-time news aggregator feels like it’s breaking down. This, in my opinion, is a good thing. The internet is better off fragmented; humanity wasn’t meant to be thrown into just one or two big rooms together. And Twitter/X was always a uniquely toxic and socially harmful platform. To the extent that Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter has broken that toxic network effect by driving liberal users to Bluesky, and worsening the general experience by deprecating external links, he has done the country and the world a great service. That said, I will be staying on X even as it degrades, as I have always promised to do. I have no plans to switch to Bluesky, which is quickly replicating some of Twitter’s more toxic traits on a smaller scale. 2. The drone future is here, it’s kind of terrifying, and there’s no avoiding itThe sky above New Jersey is suddenly alive with drones, and nobody knows why (there are a ton of theories and no answers yet). The fact that lots of people panicked — mistaking planes for drones, sending up their own drones to add to the confusion, and so on — should not obscure the fundamental reasonability of the panic. Drones have changed our physical world in important ways, and regular people are just waking up to how big of a change it is. That awakening is long overdue. I’ve been yelling for over a decade that drones are going to change everything. I often talk about how they’ll change the battlefield, but in a post in February 2023 I talked about how they’ll change life behind the front lines, and life during peacetime as well: The basic idea here is that because drones are cheap to make in large numbers and hard to detect, they can easily penetrate peacetime air defenses that would easily catch and intercept manned aircraft. This means that every city and town and neighborhood is now vulnerable to approach by drones — we’re just not going to put radars, electronic warfare devices, and point defense cannons on every city block in the country. If drones want to get close to you, they can. People in New Jersey are panicking because this fact is just now sinking in. The drones that buzzed the state — and that buzz military bases with increasing regularity — appear not to be armed. But what happens when they are? In 2017, a sci-fi short film called “Slaughterbots” explored what could happen when weaponized drones begin to fly through our cities:  In fact, this is already a reality for Ukrainians living in the war-torn city of Kherson. Russians are using drones to hunt civilians:

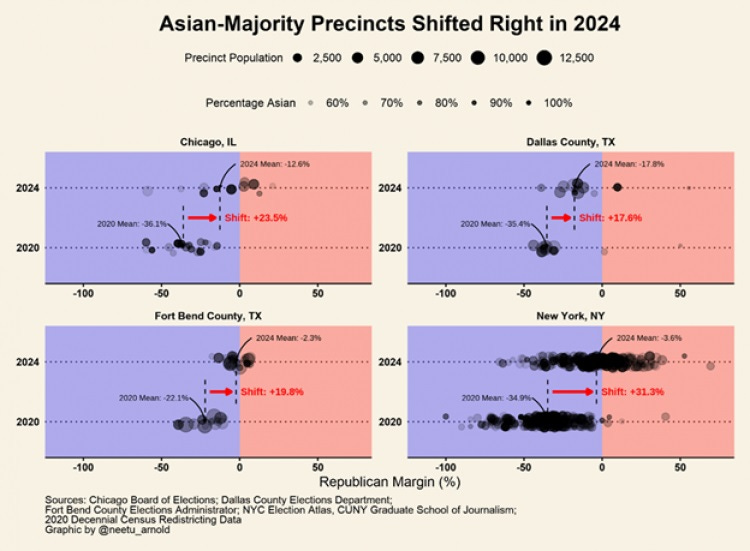

This is not really different from the terror bombing of cities, which was already a familiar feature of modern war. But whereas the RAF could shoot down or chase away Nazi bombers, it’s just very hard to defend civilian areas against swarms of drones — as the people in New Jersey are no doubt realizing. And what happens when assassins get hold of drones that can recognize people’s faces with AI and kill or spy on them from a distance? Already some super-rich people are starting to equip their yachts with anti-drone defenses. Like it or not, the drone future is here, and we all have to deal with it. Now if only all the drone batteries weren’t made in China… 3. Yes, Asian voters shifted to the rightOne of the less-discussed results of the 2024 election was that Asian voters shifted toward the GOP (this was less-discussed because most people were focusing on Hispanic voters). Some people tried to argue with this, claiming that exit polls are unreliable. But precinct-level data agrees:

Nowhere is this shift more apparent than in New York City. Politico has the story:

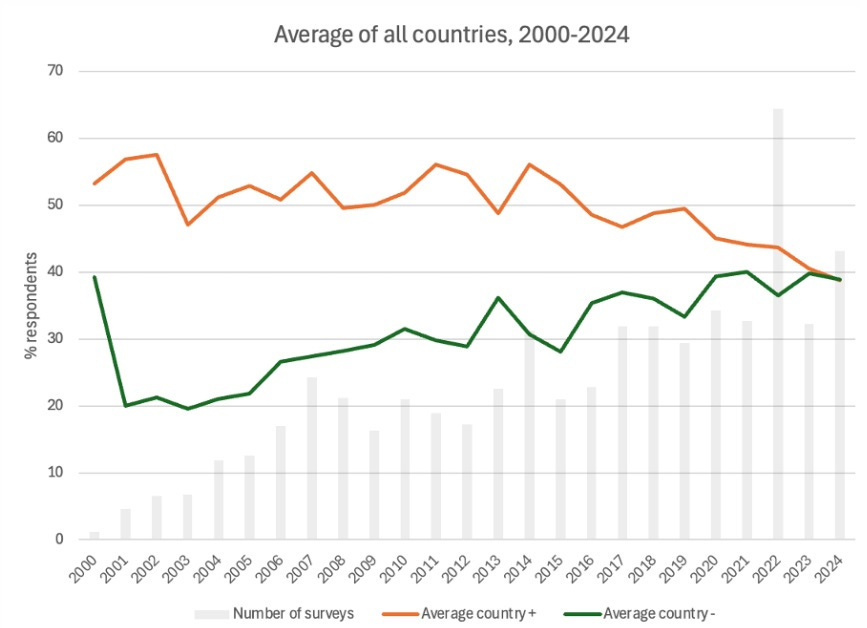

Everyone — including my guest poster Dhaaruni Sreenivas — seems to agree that the three big issues driving Asians away from the Democrats are violent crime, meritocracy, and inflation. Democrats still seem either not to understand this, or not to take it seriously. I think there’s an impulse to hide from these facts by pretending that very progressive Asian groups, activists, or writers are representative of a broad, homogeneous “Asian community” in the U.S. But broad demographics aren’t really communities, and the very progressive Asian leaders who have the ear of Democratic staffers, donors, and politicians are often not very representative at all. A related problem is the lack of highly visible conservative Asian activists and groups. The rightward shift has flown under the radar, appearing only on election day. Even the group Students for Fair Admissions, which successfully sued on behalf of Asian college applicants and got the Supreme Court to end affirmative action, was started by a white guy, Edward Blum. There are right-wing Asian folks, like Kash Patel and Vivek Ramaswamy, but they aren’t seen as the face of conservative Asian America, and I don’t think they want to be seen that way. What would be really nice is if Democrats were more able to see demographic groups as collections of individuals rather than as “communities” represented by prominent activists. As it is, conservative Asian Americans are basically illegible to the party. But they are there nonetheless, and they vote. 4. Global opinion of China has deterioratedI occasionally quote Pew polls of China, which show that the country’s reputation has deteriorated sharply since the late 2010s. China’s defenders point out that Pew’s surveys don’t cover most of the developing world, which tends to be more supportive of China. But a really thorough “survey of surveys” by the folks at the Asia Society, which covers almost every country in the world, confirms that China’s image has deteriorated across much of the globe since the mid-2010s:

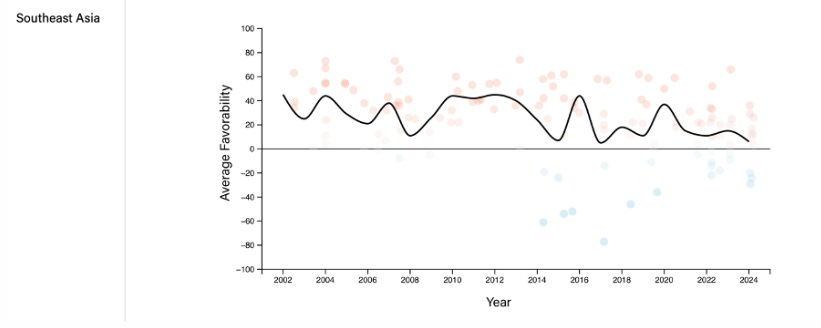

For example, Southeast Asia still has a slightly positive view of China overall, but less so than in past years:

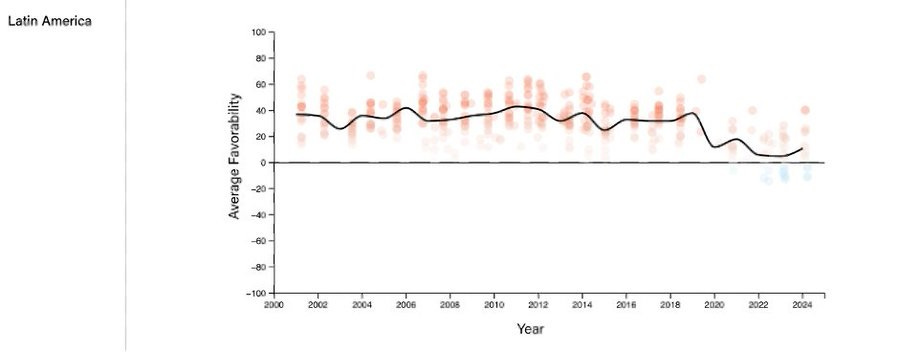

And the same is true of Latin America:

African views of China have also seen a modest deterioration, though they remain very positive. Then again, Africa is also the most pro-U.S. region on Earth, at least as far as polls go. Most importantly, opinions of China have become much more negative in a bunch of key “Global South” countries — India, Brazil, and Iran. Turkish opinion remains negative as well. There are two regions where China’s image has improved a bit lately — the Middle East and Central Asia. But overall, the Global South is becoming more skeptical of China. It’s really not hard to understand these opinion shifts. As China’s military power grows and as it becomes more assertive and even aggressive on the world stage, other countries are becoming warier of it. Rising great powers don’t always use their strength for wars and conquest, but historically it’s very common. But regions that see China as a counterweight to another powerful country that they’re on bad terms with — Russia in the case of Central Asia, the U.S. in the case of the Middle East — tend to look at Chinese power more benignly. What I wonder is how the Second China Shock is going to affect all this. China is probably using industrial overcapacity and a flood of exports to try to forcibly deindustrialize its rivals in the developed world. But in doing so, it’s also threatening to forcibly industrialize a bunch of developing countries that might otherwise be favorable to it. That could just pour fuel on the fire of China’s declining reputation in the developing world. 5. “Polycrisis” and “neoliberalism”I’ve written pretty negatively about the idea of a “polycrisis”: Basically, there are always a lot of problems in the world, and the media is always happy to deliver them right to your doorstep in order to drive engagement. And so there’s a natural tendency to read the news and think that the world is going to Hell in a handbasket. But these problems aren’t all related, and in fact sometimes some of them help ameliorate some of the others. Brad DeLong, however, does not see it that way. He looks out at the world and thinks that “polycrisis” is a good word to describe it. In a series of several posts (Post 1, Post 2, Post 3, Post 4) he makes a fairly convincing case that many of the major problems in our world stem from a single broadly defined cause: the failure of “neoliberal” approaches to economic policy and global governance. Instead of quoting from Brad’s posts, I’ll try to summarize his case. Basically, he argues that leaving everything to the market after 1970 resulted in a number of crises:

This is a very strong case. And I’d go even further and say that this is the best and most reasonable articulation of 21st century economic progressivism that I’ve seen yet. Certainly it’s a lot more persuasive than your average Guardian column, Roosevelt Institute conference, or Daron Acemoglu book. And yet I think there are still several distinct flaws in Brad’s case. Most importantly, criticizing the act of “leaving things to the market” implies that at least in hindsight there was some obviously preferable government-directed alternative on the table. Often there was not:

I do agree that America should have implemented a better social safety net earlier, but I think the one we crafted was ultimately not that bad — we devote more of our GDP to public social spending than Canada or Australia. I do agree that allowing finance to run rampant and crash the economy in 2008 was bad, but I also note that Europe and Japan suffered similar or even worse crises even though they kept their financial systems centered on banks, protected their economies, and promoted manufacturing. They also saw significant rises in poverty and inequality — sometimes steeper rises than the U.S., though from a lower base. So while I agree with Brad that the economic approaches of the 20th century have failed in ways that have brought about a number of major challenges, I also think it’s far from clear that those approaches were a huge mistake. You can call the exposure of the flaws in the “neoliberal” order a “polycrisis”, but that doesn’t mean we could have avoided that crisis. Yes, we made some mistakes, and yes, Milton Friedman’s worldview was seriously flawed. But I just don’t see any way that we could have extended the world of 1965 for another hundred years. 6. Yes, illegal immigration does strain local government financesOverall, illegal immigration probably doesn’t have a big economic effect. Lots of studies of poor refugees show that they don’t reduce real wages for the native-born. The reason is that immigrants of any kind represent both a positive labor supply shock and a positive demand shock for all kinds of products. This is also why mass deportation probably wouldn’t have a big effect on the economy overall. But “overall” masks a lot of local differences. One way illegal immigration — or any wave of low-skilled migration — really can cause difficulties is by draining local governments of funds. Poor newcomers have to be housed somewhere, and their kids have to be educated, and local governments typically shoulder much of this burden. You can argue for cutting local services to poor migrants, but then you can end up with a bunch of people on the street and teenagers running amok. When the city pays for housing and education for a ton of poor newcomers, that tends to cost a lot of taxpayer money. If the newcomers get jobs and pay taxes, that can make up for a lot of it. But if a city’s labor market isn’t firing on all cylinders, and the newcomers can’t all quickly get jobs, the city’s finances could be in trouble. That’s pretty simple intuition, but it’s always good to go out and test intuition against data. That’s what Cornaggia et al. do in a new paper on the local fiscal impacts of unauthorized immigration. They find exactly the expected results:

Here, “higher yields” means a bigger local deficit, since borrowing more means you have to offer more interest on the local government bonds. So the authors are saying that when the local economy is humming along, illegal immigrants get jobs, and then they pay taxes that offset the services they consume. But most cities aren’t humming along quite that much — when illegal immigrants show up there, the city has to go into the red to pay for them. The methodology in this paper is pretty standard — look at specific waves of illegal immigration due to specific events like wars, and then compare cities that are existing enclaves for the immigrant ethnicity (and thus tend to take in more of the same folks) with other cities, and observe the differences. There can be problems with that methodology, but those are unlikely to be an issue in this case — the fact that a great local economy tends to draw in illegal immigrants doesn’t invalidate the main finding, which is that illegal immigration strains local finances if the economy isn’t great. Anyway, this paper pretty much confirms that the migrant crisis we saw in New York City in 2022-23 — which made a lot of New Yorkers mad and probably pushed the city toward the Republican party — is the typical result of a flood of illegal immigration.¹ Democrats and progressives should understand that even if illegal immigration doesn’t hurt wages at the national level, it can be very disruptive and difficult at the local level. People aren’t crazy for getting mad at that. 7. Lessons from the sudden diminishment of Iranian powerIranian power in the Middle East seems to have suddenly suffered a partial collapse. Iran has always relied on a series of proxies to do its dirty work in the region, rather than committing its own forces. For a while, most of these proxies looked very capable, but then suddenly most of them collapsed. Hamas has been seriously diminished by Israel’s counteroffensive in Gaza since October 7th. Hezbollah has been dramatically weakened by a series of Israeli surgical strikes, forced to withdraw its forces away from the Israeli border, allowing the regular Lebanese army to take over in southern Lebanon. And most importantly, the government of Bashar al-Assad was swiftly defeated by Turkish-backed rebel forces in a lightning offensive, robbing Iran both of a major ally and of its routes to resupply Hezbollah over land. This leaves Iran with only two functional proxies left — the Houthis in Yemen, and a bunch of Shia militias in Iraq whose utility to Iran is dubious. The Houthis are formidable and have managed to impede global commerce, but this has done little to help Iran. What can we learn from this sudden Iranian reversal? I think the main lesson here is that getting directly involved isn’t always the right choice for the U.S. A lot of people excoriated Barack Obama at the time for failing to get directly involved in Syria, but that turned out to be the right decision in the long run. Over time, the brutality and ineffectuality of the Assad regime brought it down, wasting large amounts of Russian and Iranian resources for little cost to the U.S. It turns out people really don’t like brutal incompetent dictators, and often you only have to wait around for them to meet their natural end. The approach of offshore balancing worked well here. The U.S.’ allies — Turkey and Israel — defeated Iran’s proxies, without the U.S. having to do much of anything. Had the U.S. chosen to send troops to take out Assad, it very well could have been us sinking into the quagmire instead of Iran and Russia, incurring the hatred of the locals in the process. Obama looks a lot smarter in retrospect. The question is how to do something similar in Europe, so that the U.S. can focus all its attention and power on the one opponent that really matters. Abandoning Ukraine is a bad idea, but Europe can and should shoulder much more of the military burden than it’s presently doing. Meanwhile, Russia’s economy is deteriorating — if Ukraine holds out, Putin’s would-be empire may eventually be defanged by its own internal weaknesses. Only in Asia does the U.S. face an opponent whose inherent stability and vitality means that we can’t just wait it out, and whose total power exceeds that of any local U.S. ally. That is why we must focus relentlessly on Asia. 1 Or a flood of legal low-skilled immigration, of course, but floods like that rarely happen under our modern system, which is mostly based on family reunification. When it does happen, it’s due to a legal refugee wave. But the federal government tries to send those refugees to places where the economy is capable of absorbing them, and helps pay for their housing and other costs. So really, the disruptive waves tend to be illegal immigration — or quasi-legal, in the case of asylum seekers who cross illegally but then get “paroled” or otherwise allowed to stay. You're currently a free subscriber to Noahpinion. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |