|

|

Creative Destruction explores thought-provoking perspectives and ideas to expand our imagination and create a better world.

There seems to be something completely wrong with our current mode of living. It’s hard to describe or pinpoint the exact feeling that I believe a growing number of people have, but here is my attempt anyway, and maybe you can relate:

I feel awake but not alive!

The following video and a bunch of similar “Is this what life is all about?”-TikToks express a similar sentiment:

The top comment on this video:

So yeah, things seem a bit strange these days! And it feels like this has been going on for a while now, but has definitely kicked in even more since COVID.

So what’s happening here, and why are we all feeling so un-alive?

Homo Oeconomicus: Economic Machines

Well, as with everything, I’d say it is quite complex…but I do think that one key root cause of this feeling might be the following:

We have become slaves of productivity and efficiency.

“Western modernity conditions us through our upbringing, education system, and work culture, to view ourselves as rational, economic machines. Homo Economicus is the water we swim in, and is the default set of instructions for how to navigate the world.” - Rob Hardy

The “Is this productive?” question has become a sort of always-present, ambient noise lingering in the back of our minds. It has become so ingrained in our brains that it’s now almost impossible for us to contemplate another way of life – an unproductive way of living.

If something isn’t productive or anti-productive, we immediately get this reaction of disdain. Even just writing the words “an unproductive way of living” feels…odd, it feels wrong…somehow. And we’re all, of course, very aware of the fact that we are suckers for productivity hacks and convenience, which we need to keep up with the daily grind and acceleration towards the infinite.

“As growth at all costs became the guiding ethic of capitalist business over the course of the 20th century, so too did the achievement of more and more become the guiding ethic of our capitalism-colored lives.” Tara McMullin

I notice this productivity mantra in all sorts of domains of my life, including when it comes to social connections. I guess Nikki Osman can relate when she writes this:

“Lately, my social life has felt more scheduled than ever. […] ‘There’s this feeling that if you’re going to make time for someone, it has to be worth it; they have to be worth it,’ she [Sheila Liming] explains. ‘And that leads to additional stakes and burdens being placed on the hanging out. Because suddenly it feels like: this person made time for me, so I’ve got to make sure it’s worth it for them. That feeling is highly detrimental to the ways we interact with each other.’”

Our Unproductive History

It’s important to note that life wasn’t always like that!

To the contrary, we only very recently – in a tiny, tiny, recent part of humanity’s history – began to choose the more productive, the more efficient way of doing something over the more meaningful, dignifying, sacred, loving, or enjoyable one.

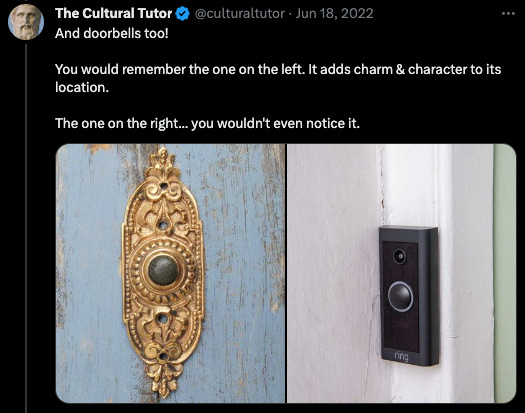

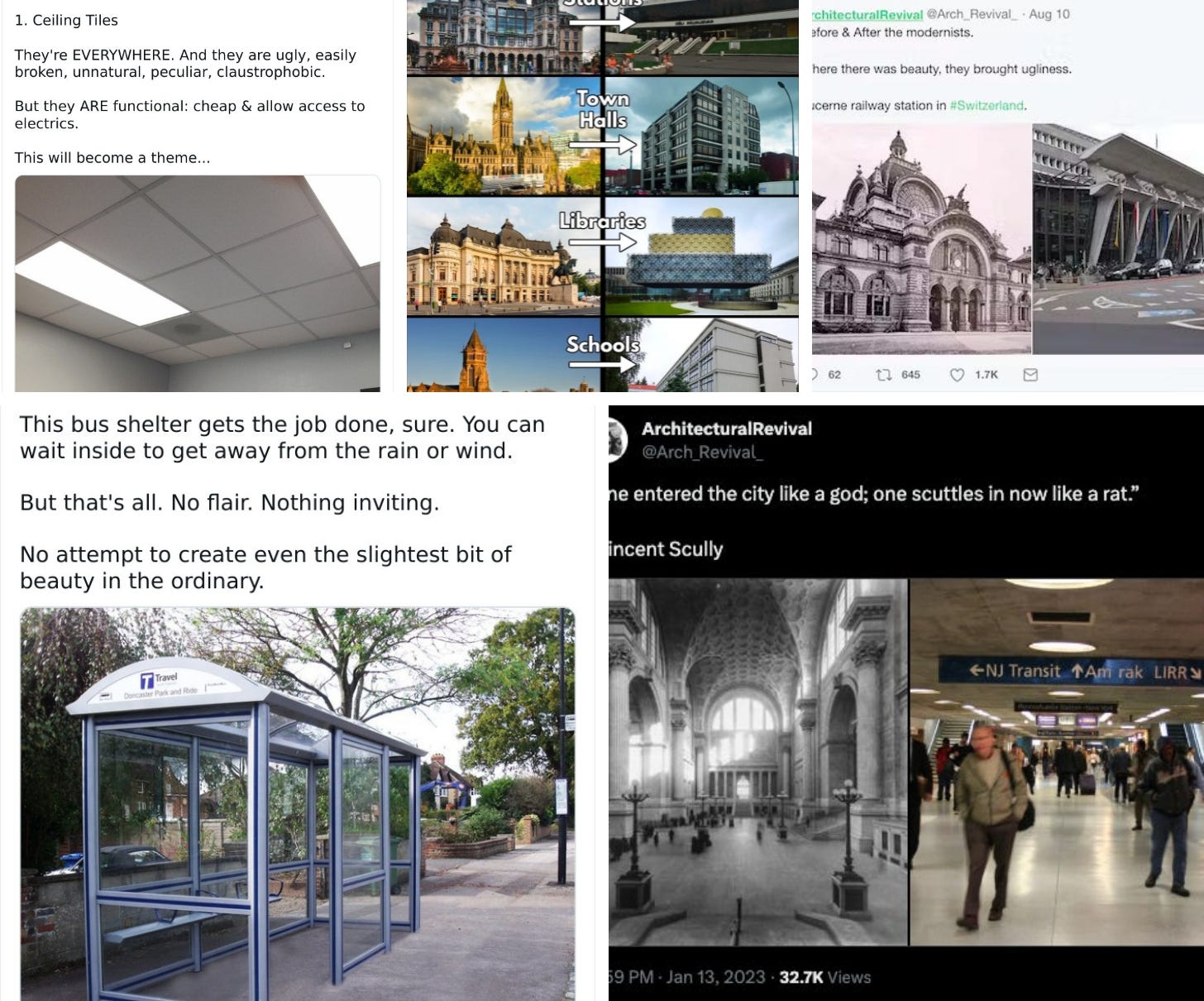

Need some evidence?! Well, simply look at old furniture and craftsmanship in general and especially architecture, and you can spot the difference between societies that weren’t as fixated on productivity and the often life-less artifacts of our modern, productivity-addicted society. And once you start looking at the world with such eyes, you’ll realize that this is what humans have done everywhere, until quite recently.

And when it comes to work, this realization adds a clarifying aspect to the age-old discussion of whether work in current times is more or less stressful than work a few centuries ago. Because the answer is no, work was probably tougher back then. But the new aspect here is that while it was tougher it wasn’t as driven by this productivity narrative (or addiction) that so deeply defines today’s work culture.

And that’s a very crucial difference! Because it has a substantially different impact on mental stress (especially when coupled with the less physical and more mental nature of most of today’s work), and I am sure that the person making the doorbell on the left (see image below) felt very different (in a positive way) than the person who made the doorbell on the right, after they were finished.

Bare Productivity

A line in a piece by Dougald Hine aptly titled “We Used to Have Fun” adds an essential nuance to this topic:

“[…] The distinctive feature of the societies to which this historical process [i.e. capitalism and industrialist mass production] gave rise is that productive activity is mostly governed by a logic that tends to strip it of things like meaning, playfulness and sociability.”

Stacey Langford from Slow Folk makes a similar point when she writes about our unnatural or limited concept of productivity:

“This past season from summer into fall has been one of the fullest in recent memory. I say full, not busy, because although it has been busy […]. This has not been that. […] These past few months have been the definition of productive in many ways. […]

So when an email landed in my inbox for a project that would pair me with a productivity specialist as opposing experts, I thought hmmm . . .

What does it say about our culture that we view slowness and productivity as mutually exclusive?

And then I thought . . . No wonder we’re all burnt out.”

Said differently, society today frames productivity in a way that only sees “doing” and excludes “being”:

“Popular books such as What You Do Is Who You Are (2019) by the venture capitalist Ben Horowitz carry the implication that being and doing are synonymous. Busyness is a badge of honour, even a sign of moral superiority. Rest, in contrast, is often treated as if it’s passive and pointless. Indeed, I’ve noticed many people hardly think of rest as its own thing. It’s just a negative space defined by the absence of work.”

To sum up, our idea of productivity is quite plain or one-dimensional.

Productivity Externalities

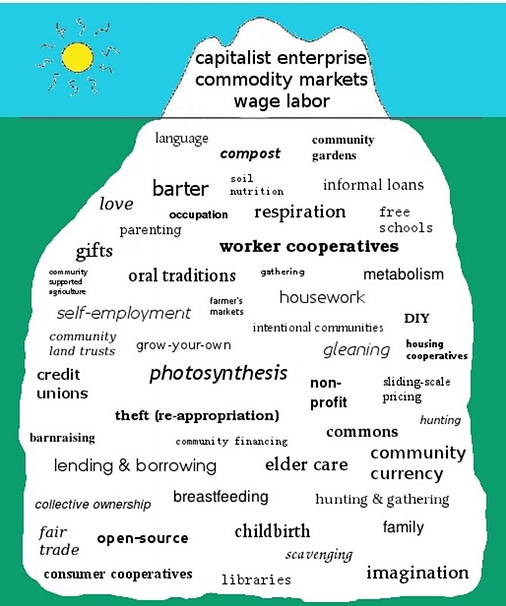

So, the problem isn’t only the pervasiveness and domination of the productivity narrative in our lives but that productivity is only measured in relation to (certain) economic gains. We don’t really think of productivity as a measure of being a great partner, parent, friend, caregiver, lover, artist, craftsperson, neighbor, creative, sibling, contemplator, savorer, rest taker, etc.

And that’s because the economy externalizes not only nature but also most other things that make life enjoyable and meaningful.

And, unfortunately, something even more perverse happens: As we end up tailoring our lives to conform to that very narrow definition of productivity, our desire for meaning, enjoyment, slowness, mental clarity, and social connections grows more and more and consequently gets exploited:

“In general, what happens is that our need for these things gets sold back to us in the form of consumption, all the things that are filed under ‘leisure’, the annual holiday in the sun, and – perhaps most toxic of all – the promise of retirement, when the lucky among us get a decade or two to travel the world and consume all the experiences it has to offer, before mortality catches up with us.” Dougald Hine

Reframing & Reclaiming Unproductivity

So what can we do? One way to step out of the productivity rat race is to reframe unproductivity and assert new value to what society often deems as unproductive moments of life – such as leisure, hanging out, doing nothing, contemplating, caretaking, creative explorations, etc.

“Withdrawal has an almost universally negative connotation in public life, where it is treated as the ultimate transgression and disdained as retreat or defeat – the very opposite of engagement. However, to withdraw is also, crucially, to repair – both to go to a place and to mend. From this perspective, withdrawal is not merely a defeatist tack; rather, it is, or can be, direct action for a restoration of intellectual life – the kind that is free to ask (to fully engage with) impertinent questions – in settings that have practically banished it, made it inaccessible, or are attempting to monitor and monetise it according to terms not of our choosing. […]

‘The classical ideal of leisure [had a] sense of freedom, superiority, and learning for its own sake.’ As Susan Neiman reminds us in Why Grow Up? (2014): ‘Plato and Aristotle believed that a life devoted to contemplation was the highest form of living.’ […]

Crucially, moments of solitude – ‘the beguiling illicit love luring us away from the proper marriage of domestic demands and delights or the civic responsibilities of citizenship’, as Patricia Hampl puts it in The Art of the Wasted Day (2018) – permit us to see into the nature of things almost as if for the first time.”

Another important step is to reclaim “unproductive” moments of life from the consumption machinery and, therefore, liberate ourselves from the productivity race. I like how Rosie Spinks talks about this in the context of what she calls the ‘The Friendship Problem’:

“[…] caretaking is a kind of liberation.

It’s liberation from the idea that we can self-optimize ourselves to the point of not needing anyone else. That if we work hard enough to survive in a competitive economy, we’ll be able to buy, order, or summon anything we might need within 24 hours, and that is somehow progress. That instead of asking for help and support from the people and friends we know — they’re too burned out, don’t want to bother them, they live too far away — we should invest heavily in self care to inoculate ourselves from needing to ask anything of anyone.

These are all ideas that capitalism loves — more people living in their own atomized fiefdoms means selling more stuff and services and meal kits to keep up with the relentless pace of life — but are fundamentally antithetical to the ways that humans are designed to flourish.”

It also reminded me of Tricia Hersey’s idea of ‘Rest Is Resistance’ which I previously shared:

“It’s counterintuitive to believe rest to be not a place to waste time but instead a generative place of freedom and resistance. We have never learned this in our culture. The thought of not doing, even for a short time, is seen as lazy and unproductive. So an explanation for rest as a form of justice is layered and nuanced. I have learned that one of the most concise and true ways to share the message of rest is to say: ‘Rest makes us more human. It brings us back to our human-ness.’ To be more human. To be connected to who and what we truly are is at the heart of our rest movement. […]

When we can begin to tap into the deep vessel of who we truly are, so many things would end about oppression. I believe the powers that be don’t want us rested because they know that if we rest enough, we are going to figure out what is really happening and overturn the entire system. Exhaustion keeps us numb, keeps us zombie-like, and keeps us on their clock.”

From Productivity To Aliveness

Lastly, I want to propose a new measure entirely, a new KPI or north star, so to say, to lead a more wholesome life. Going back to the initial attempt of me describing this zeitgeisty feeling – I feel awake but not alive! – I think what we need to do is to…

…look for what makes us feel alive instead of what makes us productive!

"Don't ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and then go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive."

Howard Thurman

I think sociologist Hartmut Rosa’s concept of resonance – which I previously explored – can give us great guidance on how to find aliveness. Kai from the Dense Discovery newsletter recently explained how Rob Hardy uses resonance in the context of creative work to gauge whether his work is on the right track, which I really like:

“Internal Resonance: How did it feel to write and publish this? Did it make me feel alive, both intellectually and somatically? Did it feel like something no one else but me could have created? Did it feel true to who I am, and who I’m becoming? Did the content of this writing matter to the deepest parts of me, beneath all of the cultural stories about who I think I should be and what I should do?

“External Resonance: How did people respond? Did I strike an emotional nerve? This goes beyond easy, legible metrics like pageviews or social media likes, or even comments, which are at best hazy approximations of external resonance. It’s about looking for signals that something genuinely MATTERED to one or more humans, and elicited a response that’s out of proportion with the average digital interaction. Lots of likes is an okay-ish signal. Lots of comments is a clearer signal. A small handful of comments or private replies from people saying they’ve never felt so seen or understood by a piece of writing – that’s the kind of thing I’m trying to discern and quantify here.”

So what I would suggest is that we attempt to apply this concept to other parts of our lives in order to really find those things, connections, places, social groups, and moments that make us feel alive rather than productive.

“Understanding these two [resonance] metrics matters more than anything I’d find in a traditional analytics dashboard. What I’m optimizing for isn’t growth, certainty, or control. It’s not the maximization of short-term revenue, reach, or influence. Instead, I’m chasing connection – both with myself and with others.” Rob Hardy

That’s it for this special Friday issue!

Please share this piece with your friends or on social media if you enjoyed it!

And there is also the possibility to ☕️ buy me a coffee if you want.

Thanks for supporting my work! 😊